Background and Anatomy

The Lisfranc joint complex is composed of the five tarsometatarsal (TMT) joints, which are important for the articulation between the forefoot and midfoot. This anatomic region is named after the 18-19th-century French surgeon Jacques Lisfranc de St. Martin. He was a field surgeon for Napoleon's army serving on the Russian front and developed a new amputation technique across the five TMT joints as a treatment for soldiers with gangrene or crush injuries to the midfoot. Now known as the Lisfranc joint, the term is used today to describe a variety of traumatic injuries to the TMT joints in the midfoot.

| Anatomy of Lisfranc joint complex |

- Medial column, or first ray, consisting of the medial cuneiform and first metatarsal

- Middle column, consisting of the second and third metatarsals and cuneiforms

- Lateral column, consisting of the fourth and fifth metatarsals and cuboid

Crucial plantar and dorsal interosseous ligaments link and stabilize the Lisfranc joint complex. The dorsal ligaments are weaker than the plantar ligaments which can explain the majority of Lisfranc injuries involving dorsal dislocations. The first of the dorsal ligaments connects the first (medial) cuneiform and base of the second metatarsal. The second connects the second (intermediate cuneiform) to the base of the second metatarsal. Lastly, the third stabilizing interosseous ligament connects the third cuneiform with the third metatarsal. The proper stabilization/maintenance of these ligaments and bones within the Lisfranc joint complex is crucial for proper function of the foot upon weight bearing. Any rupture of the interosseous ligaments or fracture-dislocation of the joint complex can destabilize the midfoot.

|

| Example of the common location of a Lisfranc fracture and ligament tear (left) and the mechanism of the Lisfranc injury with displacement of the second metatarsal (right). |

| Most common mechanisms of Lisfranc injury from Shahin Sheibani-Rad, MD, MS et al. 2012 |

Diagnosis

| Weight-bearing X-rays showing an example of a normal Lisfranc joint (left) and a dislocated Lisfranc joint (right). |

|

| Weight-bearing X-rays of obvious and subtle diastasis/dislocation of the Lisfranc joint. |

Treatments

Every Lisfranc injury is unique so it is difficult to determine when to surgically intervene or treat non-operatively with conservative measures. The course of treatment is usually based on the severity of instability/displacement in the midfoot upon stress or weight bearing and the type of Lisfranc injury. The degree of midfoot instability is categorized by the amount of diastasis in the Lisfranc joint:

- Stage I (a sprain <2 mm)

- Stage II (2-5 mm)

- Stage III (>5 mm)

The type of Lisfranc injury can be classified into purely ligamentous and combined ligamentous and osseous (fracture-dislocations). Conservative treatment is usually advised for Stage I subtle, ligamentous non-displaced Lisfranc injuries. It involves non-weight bearing in a cast or medical boot for 6-8 weeks. Most of the literature agrees that when Lisfranc injuries, whether it is ligamentous or fracture-dislocations, have larger displacement and greater instability (Stage II and IIII) they should be treated operatively.

The two main types of surgical treatment include open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) and primary arthrodesis (fusion). ORIF involves the rigid fixation and anatomic reduction of the Lisfranc joint with hardware such as titanium screws, bridging plates, K-wires, or even "synthetic ligaments" (a.k.a. mini-tightrope/suture button). The hardware acts to stabilize the joint complex and allow the ligaments and soft tissue to heal. Often, the hardware is left in the foot for 4-6 months until the stabilization of the midfoot is sufficient and then it is removed. In some cases, the hardware remains permanently unless it causes pain to the patient or breaks.

Primary arthrodesis surgically fuses the afflicted Lisfranc joints to stabilize the midfoot. The bones in the midfoot are fused by first debriding the injured joints then grafting some of the patients own bone (often from the fracture site, heel, or hip) into the joint space. The joint is closed and stabilized with titanium screws or plate. The number of bones/joints fused relies on the severity and displacement of the injury. If the extent of intraarticular and ligamentous damage is severe in a joint, that joint is usually fused.

The two main types of surgical treatment include open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) and primary arthrodesis (fusion). ORIF involves the rigid fixation and anatomic reduction of the Lisfranc joint with hardware such as titanium screws, bridging plates, K-wires, or even "synthetic ligaments" (a.k.a. mini-tightrope/suture button). The hardware acts to stabilize the joint complex and allow the ligaments and soft tissue to heal. Often, the hardware is left in the foot for 4-6 months until the stabilization of the midfoot is sufficient and then it is removed. In some cases, the hardware remains permanently unless it causes pain to the patient or breaks.

Primary arthrodesis surgically fuses the afflicted Lisfranc joints to stabilize the midfoot. The bones in the midfoot are fused by first debriding the injured joints then grafting some of the patients own bone (often from the fracture site, heel, or hip) into the joint space. The joint is closed and stabilized with titanium screws or plate. The number of bones/joints fused relies on the severity and displacement of the injury. If the extent of intraarticular and ligamentous damage is severe in a joint, that joint is usually fused.

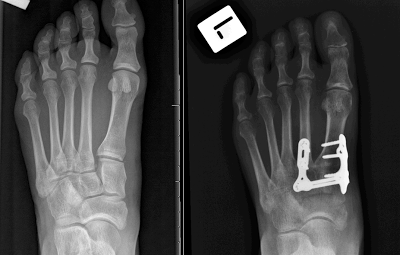

|

| X-ray images of foot with Lisfranc injury pre-op (left) and post-op after ORIF with metal plates and screws (right). |

The preferred type of surgical intervention for Lisfranc injuries has been a topic of debate. There are many factors which are taken into account when deciding on ORIF or primary arthrodesis. Most of the studies advocate for ORIF in:

- Less severe injuries

- Non-chronic injuries

- Patients who are young

- Subtle injuries with slight displacement

- Injuries with little to no articular damage within the joint

- Injuries in high-level athletes

Indications for primary arthrodesis are as follows:

- Severe Lisfranc fracture-dislocations

- Injuries in older patients

- Failed previous ORIF surgery or any Lisfranc injury with persistent pain

- Presentation of severe osteoarthritis in the joint complex

- For a long term misdiagnosed or chronic injury

ORIF

Most of the current literature supports ORIF as the primary surgical treatment for Lisfranc injuries that are not severe. It has been shown that ORIF can provide a successful recovery, return to activity, and a good functional outcome following the indications for ORIF of the Lisfranc Joints. Depending on the type of Lisfranc injury, screws, plates, K-wires, or a mini-tightrope can be used to fixate the joint. Although past surgical treatments have mainly involved screws, plates, and K-wires, recent studies have shown that for some types of Lisfranc injuries a mini-tightrope/suture button is useful and has excellent outcomes. In particular, the use of a mini-tightrope/suture button has proven successful in athletes with subtle Lisfranc injuries.

There is often no need to remove hardware after healing is completed (the mini-tightrope is always permanent) unless there is a hardware failure of the patient experiences pain from prominent screws. However, ORIF can frequently lead to the formation of post-traumatic arthritis within the Lisfranc joint, which can prove to be debilitating and require secondary arthrodesis surgery. Arthritis is usually created from articular damage from the initial injury or from the placement of stabilizing screws through the articular surface in the Lisfranc joint. In order to circumvent the latter of these causes, it is common for surgeons to utilize titanium plates to bridge and stabilize the joints without disrupting the joint surfaces. Nonetheless, some studies have noted that greater than 50% of ORIF patients go on to have arthritis within the affected Lisfranc joint(s). There is also evidence that in purely ligamentous injuries treated with ORIF the healing of the ligaments did not provide sufficient strength to maintain the stability of the midfoot. The compromised integrity of the Lisfranc joint can lead to pain, deformity of the foot, or post-traumatic arthritis. In such cases, a patient with a failed ORIF usually requires secondary surgery involving arthrodesis of the affected joints.

Arthrodesis

In the past, it was thought arthrodesis was done as a last resort for a failed ORIF or very severe fracture-dislocation. However, in more recent studies there has been some controversy as to whether it is better to treat primarily ligamentous Lisfranc injuries with ORIF or arthrodesis. A number of studies provide evidence that primary arthrodesis could provide a better outcome than ORIF in purely ligamentous injuries. One study found that a sample of patients that underwent primary arthrodesis and ORIF for purely ligamentous injuries returned to 92% and 65% of their pre-injury activity level, respectively. Another study compared the postoperative pain levels in a group of arthrodesis and ORIF patients. They found that the arthrodesis group had a mean AOFAS post-surgical pain score (out of 100) of 86.9 compared to 57.1 in the ORIF group. However, other studies have noted that they have found no significant difference between the clinical outcomes of patients who underwent ORIF and primary arthrodesis.

There is agreement that a primary arthrodesis can potentially prevent the development of a painful, deformed foot, in the case of a failed ORIF, and the need for future surgery. Primary arthrodesis has been found to result in statistically fewer follow-up surgeries compared to that of ORIF if hardware removal is performed. In addition, patients who have been treated with arthrodesis for primarily ligamentous Lisfranc injuries have been shown to function as well as those treated with ORIF. Nonetheless, arthrodesis or partial arthrodesis of the Lisfranc joint has its drawbacks. When the medial or middle column of the midfoot is fused the Lisfranc joint becomes rigid. Therefore, much of the energy that was once absorbed by the Lisfranc joint upon weight-bearing is distributed to adjacent, unfused joints in the foot. Over time, this can lead to the development of arthritis in the adjoining joints or the increased risk of stress fractures. Arthrodesis of the medial column also inhibits mobility in the midfoot, which is thought to be necessary for proper function of the foot when running. For this reason, arthrodesis is usually not the preferred treatment for patients who want to return to high-level athletics. Yet, there have been studies that found the return to athletics in a group of young patients with primary arthrodesis was very high.

| Adapted from MacMahon et al. 2016. Pre- and postoperative activity levels of patients in a study who received primary arthrodesis. |

Recovery

Recovery from a Lisfranc injury, whether by means of conservative or operative treatment, is a slow process. For the Stage I non-displaced Lisfranc injury, conservative treatment usually involves non-weight bearing in a cast or medical boot for 6-8 weeks. Then the patient is transferred into a partial weight bearing walking boot for another 2 weeks and then full weight bearing in the boot for 4-6 weeks. Physical therapy is advised after the first 6-8 weeks and a transfer to stiff soled shoes and orthotics is recommended after 6-8 weeks in the boot. In total, the recovery period last approximately 3-4 months.

The recovery period for operative treatment of Lisfranc injuries is similar to that of conservative approaches. Regardless of the type of surgery (ORIF or arthrodesis), the patient is put in a non-weight bearing splint for 10-14 days at which point the split is removed and the stitches are removed from the surgical incision. Once the stitches are removed, a hard cast or air cast is placed on the foot. The cast is removed after 4-6 weeks and weight bearing X-rays are taken to ensure hardware has not moved or become broken. The patient is then placed in a partial weight-bearing walking boot for 7-14 days. Full weight bearing is permitted with the boot after this period and is continued for another 4-6 weeks. More weight bearing X-rays are taken once the boot is removed, and the patient is then transferred into a supportive, stiff-soled shoe with orthotics.

In both the conservative and surgical treatments, physical therapy can be initiated after the transfer to partial weight bearing in a boot. Therapy usually focuses on regaining proper gait by strengthening the leg, calf, and ankle of the affected leg. The intrinsic muscles of the foot are also worked to strengthen and regain function.

Conclusion

Conclusion

The Lisfranc joint complex provides stabilization to the midfoot and arch upon weight bearing and normal gait. Any tear, rupture, or fracture to the Lisfranc joint can compromise the integrity of the midfoot leading to malalignment and diastasis within the Lisfranc joint. The common mechanisms of injury to the Lisfranc joint include high-energy injuries such as motor vehicle accidents or falls from heights and low-energy injuries that often occur in athletics when the foot is twisted or bent under pressure.

Timely diagnosis and treatment of a Lisfranc injury are imperative for a good recovery. Weight-bearing X-rays are standard for determining if a Lisfranc injury exists. The weight-bearing X-rays can indicate diastasis or malalignment in the midfoot that is associated with Lisfranc fracture-dislocations. MRI imaging can also be useful to determine the amount of damage to ligaments, soft tissue, and joints that are not visible on X-ray. However, the complexity of the Lisfranc injury makes it easy to misdiagnose or miss altogether. Subtle Lisfranc injuries are particularly difficult to diagnose.

Treatment of Lisfranc injuries is related to the degree of instability/separation in the Lisfranc joint complex. Subtle non-displaced (usually Lisfranc sprains) do well with conservative treatment. More severely displaced injuries require operative treatment to realign/stabilize the joint and heal ligaments. The two main surgical treatments for Lisfranc are ORIF and primary arthrodesis. The severity/type of the injury, the amount of joint damage, and age are the main factors when deciding whether to proceed with ORIF and arthrodesis. ORIF and arthrodesis have both proven to provide good functional outcomes and a relatively high return to activity. Complications of ORIF include the development of arthritis in the Lisfranc joint and possible failure to provide adequate stabilization to the midfoot. Complications of arthrodesis include the development of arthritis in joints adjacent to the fused joints, increased risk of fractures, and a smaller range of motion/function of the midfoot.

References and Resources

Brin, Y. S., Nyska, M., & Kish, B. (2010). Lisfranc injury repair with the TightRope™ device: a short-term case series. Foot & ankle international, 31(7), 624-627.

Charlton, T., Boe, C., & Thordarson, D. B. (2015). Suture button fixation treatment of chronic Lisfranc injury in professional dancers and high-level athletes. Journal of Dance Medicine & Science, 19(4), 135-139.

Brin, Y. S., Nyska, M., & Kish, B. (2010). Lisfranc injury repair with the TightRope™ device: a short-term case series. Foot & ankle international, 31(7), 624-627.

Charlton, T., Boe, C., & Thordarson, D. B. (2015). Suture button fixation treatment of chronic Lisfranc injury in professional dancers and high-level athletes. Journal of Dance Medicine & Science, 19(4), 135-139.

Cochran, G., Renninger, C., Tompane, T., Bellamy, J., & Kuhn, K. (2016). Treatment of Low Energy Lisfranc Joint Injuries in a Young Athletic Population Primary Arthrodesis Compared with Open Reduction and Internal Fixation. Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine, 4(7 suppl4), 2325967116S00172.

Faciszewski, T., Burks, R. T., & Manaster, B. J. (1990). Subtle injuries of the Lisfranc joint. The Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery, 72(10), 1519-1522.

Hawkes, N. C., Flemming, D. J., & Ho, V. B. (2007). Subtle Lisfranc injury: low energy midfoot sprain. Mil Med, 172(9), 12-3.

Lewis Jr, J. S., & Anderson, R. B. (2016). Lisfranc Injuries in the Athlete. Foot & Ankle International, 37(12), 1374-1380.

MacMahon, A., Kim, P., Levine, D. S., Burket, J., Roberts, M. M., Drakos, M. C., ... & Ellis, S. J. (2016). Return to sports and physical activities after primary partial arthrodesis for Lisfranc injuries in young patients. Foot & ankle international, 37(4), 355-362.

Mulier, T., Reynders, P., Dereymaeker, G., & Broos, P. (2002). Severe Lisfrancs injuries: primary arthrodesis or ORIF?. Foot & ankle international, 23(10), 902-905.

Panagakos, P., Patel, K., & Gonzalez, C. N. (2012). Lisfranc arthrodesis. Clinics in podiatric medicine and surgery, 29(1), 51-66.

Panchbhavi, V. K., Vallurupalli, S., Yang, J., & Andersen, C. R. (2009). Screw fixation compared with suture-button fixation of isolated Lisfranc ligament injuries. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 91(5), 1143-1148.

Panchbhavi, V. K., Vallurupalli, S., Yang, J., & Andersen, C. R. (2009). Screw fixation compared with suture-button fixation of isolated Lisfranc ligament injuries. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 91(5), 1143-1148.

Raikin, S. M., Elias, I., Dheer, S., Besser, M. P., Morrison, W. B., & Zoga, A. C. (2009). Prediction of midfoot instability in the subtle Lisfranc injury. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 91(4), 892-899.

Sheibani-Rad, S., Coetzee, J. C., Giveans, M. R., & DiGiovanni, C. (2012). Arthrodesis versus ORIF for Lisfranc fractures. Orthopedics, 35(6), e868-e873.

Sherief, T. I., Mucci, B., & Greiss, M. (2007). Lisfranc injury: how frequently does it get missed? And how can we improve?. Injury, 38(7), 856-860.

Wadsworth, D. J., & Eadie, N. T. (2005). Conservative management of subtle Lisfranc joint injury: a case report. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 35(3), 154-164.

Image sources

http://www.aafp.org/afp/1998/0701/afp19980701p118-f4.jpg

http://www.footeducation.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/08/Figure-1B-Lisfranc-Injury-x-ray-image-Normal-vs-Injured-300x225.png

http://orthoinfo.aaos.org/figures/A00162F01.jpg

http://www.braceability.com/foot-problems-foot-disorders/lisfranc-injury-fracture

http://www.federicousuelli.com/usuelli/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/fig-11.jpg

https://i.ytimg.com/vi/xuC7dnG2_Xg/maxresdefault.jpg

https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEj9oTZdwE8eZl8wL2lvMNGKnogjWaJMjlPBpu3Ar8BoK1j3L4v7tlRiYAg_yHc7K2mWsO5YpZcscrnnmzTGHIxpNiH_3WLYfc_EqnrljvQ0QVzVeHEibjWhInJTn3IkwHoP5xJw5vGig6A/s1600/Lisfranc+4.png

Image sources

http://www.aafp.org/afp/1998/0701/afp19980701p118-f4.jpg

http://www.footeducation.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/08/Figure-1B-Lisfranc-Injury-x-ray-image-Normal-vs-Injured-300x225.png

http://orthoinfo.aaos.org/figures/A00162F01.jpg

http://www.braceability.com/foot-problems-foot-disorders/lisfranc-injury-fracture

http://www.federicousuelli.com/usuelli/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/fig-11.jpg

https://i.ytimg.com/vi/xuC7dnG2_Xg/maxresdefault.jpg

https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEj9oTZdwE8eZl8wL2lvMNGKnogjWaJMjlPBpu3Ar8BoK1j3L4v7tlRiYAg_yHc7K2mWsO5YpZcscrnnmzTGHIxpNiH_3WLYfc_EqnrljvQ0QVzVeHEibjWhInJTn3IkwHoP5xJw5vGig6A/s1600/Lisfranc+4.png